We have received many questions from our younger followers and those who are young at heart. Here’s a collection of some of the more common questions that have been asked.

Q: Which dinosaurs do you hope to find?

A: We hope to find an Abelisaurid theropod, a horned/ornamented predatory dinosaur or a titanosaurian sauropod, a large herbivorous dinosaur. Dinosaurs are rare in the rocks we plan to explore. The most likely kind of dinosaur we may find would be an ornithopod, a small-bodied herbivorous dinosaur.

Q: How do you know what color the dinosaurs were?

A: We don’t for sure! We compare the dinos with living animals from similar habitats to estimate what color they might have been.

Q: What would you do if you found a real living dinosaur? Would you be scared?

A: Because birds are living dinosaurs, we would not be at all surprised! I hope we see some penguins and albatross. (If we found a living non-avian dinosaur, we would be VERY SURPRISED!!)

Q: What does it feel like to find a dinosaur bone? Is it exciting?

A: It is exciting! When you find a fossil, you are the first living creature to see it since it died! A couple of things that never fail to inspire awe: Remembering that the fossil you’re holding used to be part of a living creature. Thinking about/trying to conceptualize the VAST timescales we study. 70 MILLION YEARS! And that’s not even super long, in the context of the history of the earth!

Q: What is your proudest accomplishment in your scientific fields?

A: Matt here: My proudest accomplishment is the co-discovery of humongous new dino in Egypt back when I was in grad school, that we named Paralititan stromeri.

Abby here: I suppose my proudest accomplishment so far is having very-nearly-finished a PhD. With any luck, that’ll soon be much less important compared to my future major accomplishments!

Q: What is your favorite discovery?

A: Abby here: My favorite discovery was a fossil mammal skull, in Wyoming. We can figure out how old a fossil is by studying the rocks it’s found in– we can compare the layers of rock (stratigraphy) to figure out which one is oldest, or use methods similar to carbon dating to get a numerical age.

Matt here — my favorite discovery that I was a part of was in Egypt in 2000, when some grad school buds and I found a new species of dino that’s one of the largest ever discovered, Paralititan stromeri.

Q: What are non-avian dinosaurs ?

A: Literally, any dinosaur that is not a bird. Birds are a living lineage of dinosaurs that survived the mass extinction that happened 66 million years ago. This a handy phrase to provide a distinction between what people normally think of as dinosaurs (those that are extinct) versus birds, which are the surviving group of dinosaurs.

Q: What is the weirdest animal you’ve found?

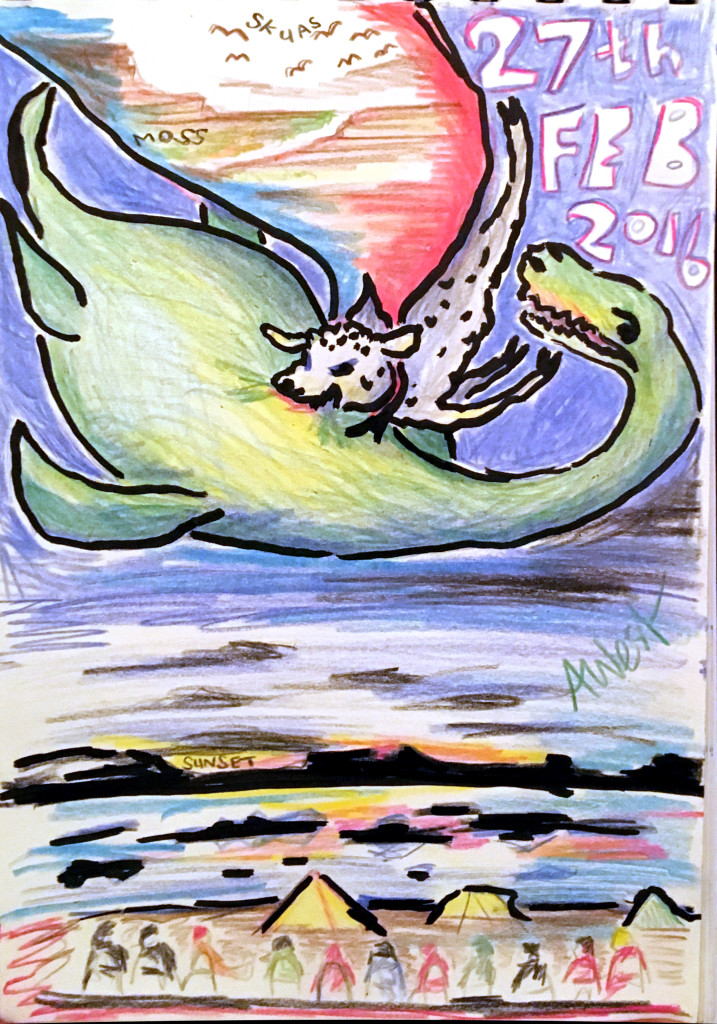

A: Matt here: To me, the weirdest animal that has been found here is, ironically, the one that would be the most familiar to us today: the duck-like bird Vegavis. It’s weird because birds living at the same time elsewhere in the world are only distantly related to modern birds (they had teeth, may have been fairly poor fliers, etc). Also the plesiosaur Morturneria is thought by some to have been a filter-feeder, which would be pretty weird. Imagine a marine reptile trying to be a humpback whale!

Q: Why did you choose this as your career?

A: Matt here. I went into paleontology because I told my parents I wanted to be a paleontologist when I was four, and never really thought of doing anything else. What made me a paleontologist? Hard work, persistence, patience, and a whole lot of luck.

Q: What’s the largest fossil you’ve seen unearthed? And what was it?

A: Matt here: I’ve had the good fortune to have helped discover two of the world’s largest dinosaurs: Paralititan in Egypt in 2000 and Dreadnoughtus in Argentina in 2005. The limb bones of those things are almost as tall (or in a couple cases, taller) than I am, and I’m 5′ 11″.

Q: Have any of your fossil ended up in museums we could visit?

A: Yes, many of us have discovered fossils that are currently on display in museums, though many of these are overseas in the countries in which they were found. For example, the bones of Paralititan are in the Egyptian Geological Museum in Cairo and those of Dreadnoughtus are in the Museo Padre Molina in Rio Gallegos, Argentina.

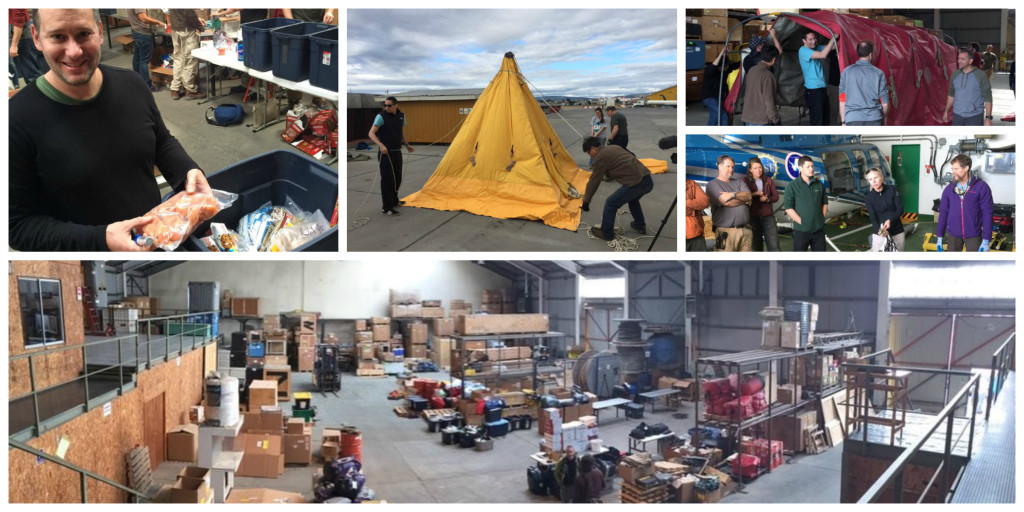

Q: How are you preserving/transporting the samples you collect?

A: All fossils are wrapped and padded for transport back to the States. Ultimately, they will become part of a museum collection.

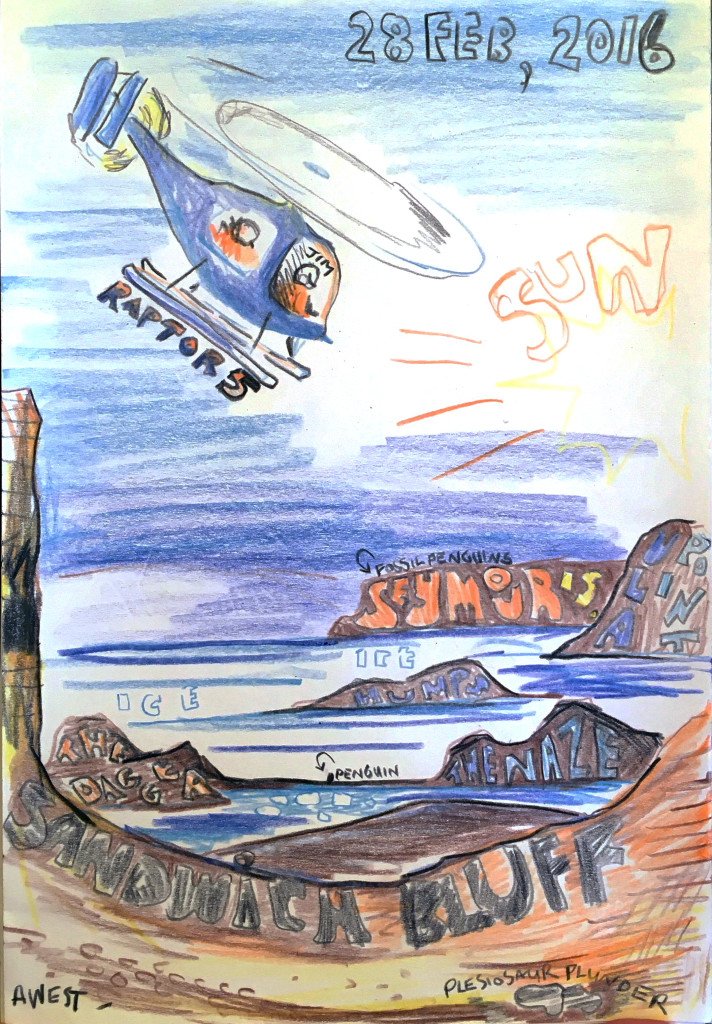

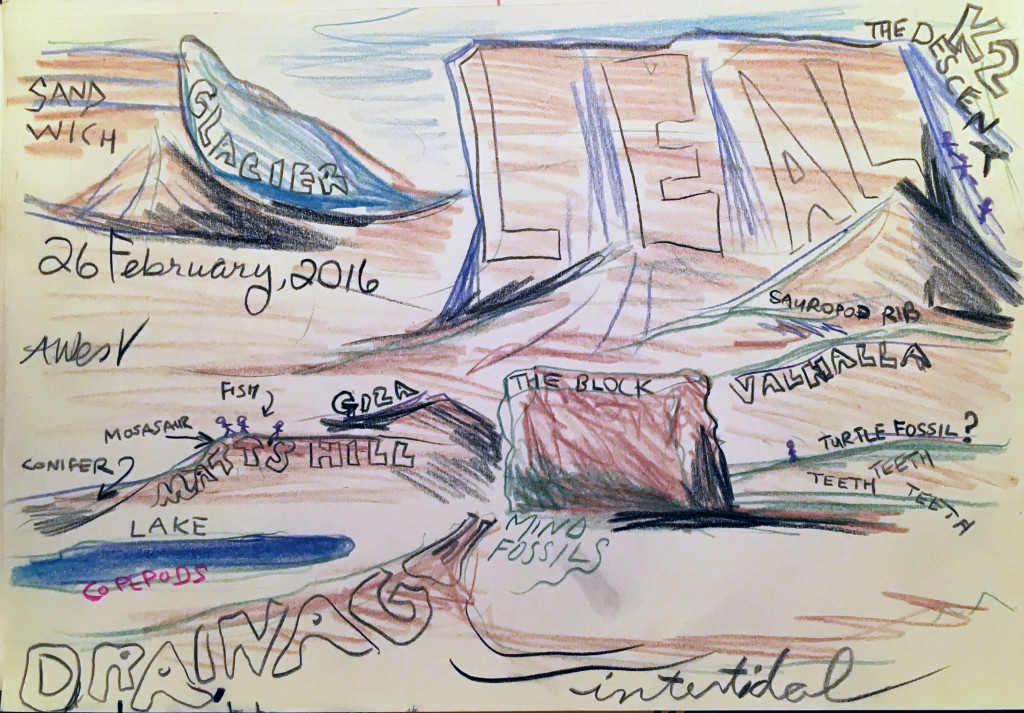

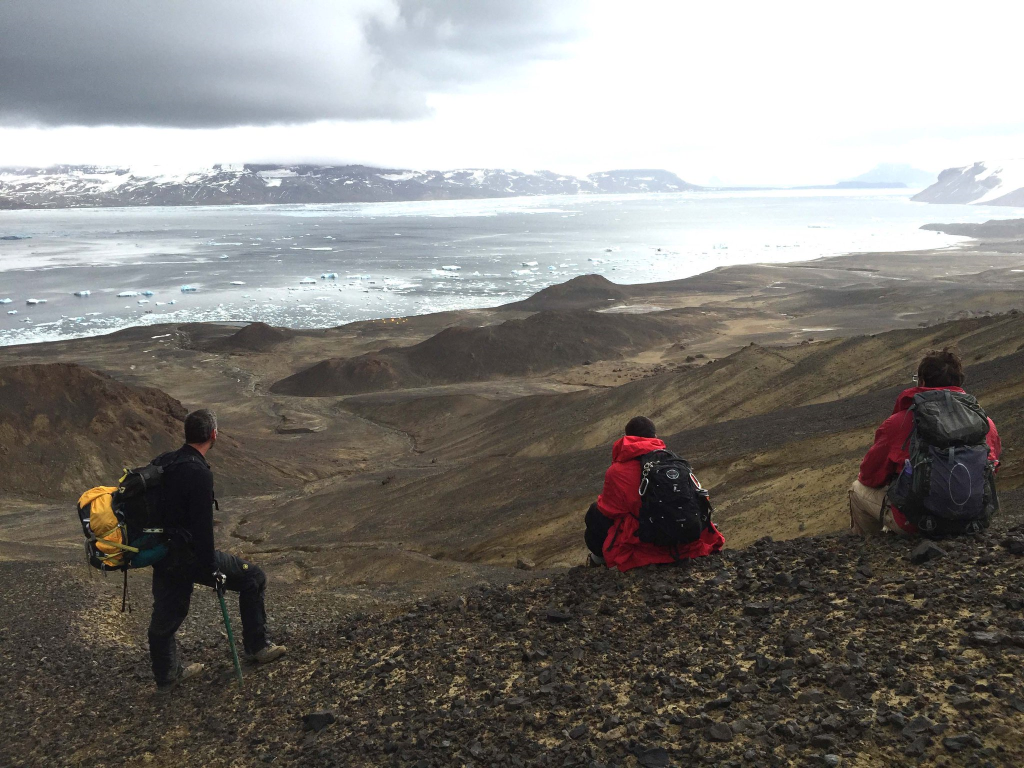

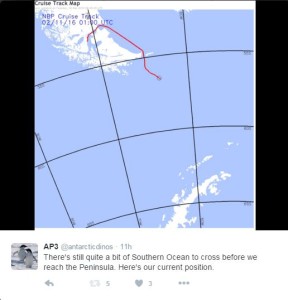

Q: Where do you stay and sleep for the trip?

A: Our permanent base is aboard the RVIB Nathaniel B. Palmer, a NSF science research ship. From there, different groups from our team will be going ashore to camp at various localities that we get to from zodiac boats and/or helicopters. We will not be going into or be based out of any of the permanent camps/bases on Antarctica.

Q: How possible is it to reconstruct dinosaurs from the DNA found in bones and insects in amber?

A: Abby here: there is a growing field of study that aims to extract and sequence DNA and protein molecules from fossils. In some of my own research, I have sequenced genes from the bones of wooly mammoths and ancient bison. Unfortunately, the maximum lifespan of DNA (before it has all decayed away) seems to be only a few hundred thousand years, so we probably won’t be able to get any DNA from the Age of Dinosaurs.

Q: What do paleontologists do when they aren’t digging?

A: When we aren’t digging, we are studying what we dug up! We compare it to what we already know, like other fossils and living animals, and we write papers to report what we found. Then we write grants to get funds to do more digging! Those of us who are students take classes and do our own research. Those of us who are professors teach classes and advise our students. Those of us who work at museums make sure our fossils find safe, happy homes where scientists like us and the public like you can see them anytime they like.

Q: Were all the major dinosaur groups on Antarctica?

A: Nope! There have been reports of hadrosaurs, ankylosaurs, ornithopods, theropods (like dromaeosaurs and several early birds) and sauropods (like titanosaurs). So far, we haven’t found any large-bodied theropods (like abelisaurs), which we might expect based on what we know about their distribution in the Late Cretaceous. We don’t expect to find some more famous Cretaceous dinosaurs like Triceratops, tyrannosaurids and pachycephalosaurs, which are known only from the Northern Hemisphere.